The Danes have stolen something very precious.

Take a walk through central Copenhagen these days and it isn’t just the tourists who you’ll hear speaking English. Turn on the TV or radio or listen to a podcast and my first language is everywhere there too, particularly if by some terrible accident your device chances upon P3 radio and you are somehow trapped and can’t turn it off. The Danish language has been chronically infected by the English variant.

There is a generational schism at work here: younger Danes are the worst offenders, older Danes bemoan the development, seeing it quite rightly as a threat to the Danish language and a sign of a diseased society on the brink of total collapse.

You'd think that, as an Englishman, I would welcome hearing my language. The more English there is, the better, surely? But no. Dammit. I haven’t spent bloody years learning how to speak bloody Danish only for the Danes to start speaking bloody English all the bloody time.

Danish is a hellishly difficult language to master. And I’m not just saying that because I have clawed my way up the North Face of that Everest, enduring years of bewildered looks and public humiliation along the way. Experts agree: in a report entitled The Puzzle of Danish, a group of cognitive and language scientists from Aarhus University and Cornell recently concluded that Danish children take two years longer to learn the past tense than their Norwegian contemporaries, even though the two languages are very closely related. The Danish kids’ vocabulary is significantly smaller too. So even Danes find their own language burdensome.

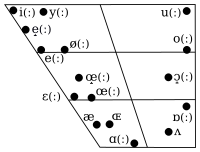

Apparently the problem lies with vowel sounds. Written Danish features eight vowels - compared to the five which we make do with in English - but somehow those eight multiply to 40 when the Danes (partially) open their mouths to speak, each of them virtually indistinguishable from the other to the normal human ear. To outsiders, Danish often sounds like it is almost entirely made up of vowels. Like something an angry farmer fresh from the dentist and still with a mouthful of anaesthetic would shout at you across a field. While throwing up.

Why don’t they pronounce your consonants properly like those nice Norwegians? Are they in a particular hurry? Too busy to enunciate? Or are they all trying to sound like Mads Mikkelsen? We all love Mads, one of the greatest actors in the world, but do the Danes realise he has a speech impediment?

Even the Swedes, with whom the Danes have conversed relatively easily (if not always amicably) for centuries, now find them incomprehensible. It’s no wonder young Danes are turning more and more to English, but for a native English speaker there is no small measure of cognitive dissonance to be experienced in hearing a Dane in full guttural, glottal-filled flow suddenly refer to their ‘roomie’ or describe someone as ‘cringe’, or something as ‘super-nice’, like there’s a glitch in their software.

University of Copenhagen researcher, Henrik Gottlieb, recently described the English influence on Danish as “a snowball, that’s not going to stop”. English has, he says, moved from EFL - English as a Foreign Language - to ESL - English as a Second Language. During his research he often meets young Danes who find it easier to use English words than Danish. Soon, he says, it won’t just be the odd loaned word or phrase, it will be entire sentences in English.

When I heard this, I got really, really cross indeed.

What is to be done? Unlike its French equivalent, L’Académie Francais, with its 40 ‘immortals’ - Peruvian Nobel prize winner, Mario Vargas Llosa, now among them - who are charged with dreaming up snappy new words for Anglo inventions like drive-thru (‘point de retrait automobile’), its Danish equivalent, Dansk Sprognævn, only really seems to monitor what’s happening in the language, like a community policeman who can merely stand by and watch a little old lady getting mugged.

Why am I so irritated by all this Anglicism? Partly, yes, it is my annoyance at having spent so much time learning another language but also because the Danes’ use of English sometimes verges on cultural misappropriation. Their indiscriminate overuse of one English word in particular has corrupted and weakened it to the point of meaninglessness.

I’m talking here about the f-word. I am not a prude when it comes to fruity language. I do not hesitate to deploy the f-bomb myself when required. But I do lament its emasculation by the Danes.

I’ve seen ‘Fuck’ in adverts, in newspaper headlines, and of course I have heard it spoken on television and radio at all times of the day by all manner of people. At music award shows, pop stars compete see how much of their acceptance speeches can be replaced by the word (like that famous scene in ‘The Wire’ where McNulty and Moreland inspect a crime scene and their entire dialogue is just ‘fuck’ back-and-forth). To native-speaking ears it sounds painfully childish. In school, teachers accept it, indeed themselves bandy it in classes. I still remember my confusion when my eldest son came home from school with his first English language text book when he was about seven, and the f-word word put in an appearance in the very first line.

Even more peculiar is the way ‘sorry’ is elbowing ‘undskyld’ aside, particularly in the public sphere. I suspect psychologists would have a field day exploring why Danes seem to find it easier to use an English apology than their own. Does it have some legal ramifications of which I am not aware?

I admit that another thing I find upsetting about all this is that it generally isn’t British-English the Danes are adopting, but thanks to the global nature of digital media and entertainment, it’s mostly the already debased, corrupted form of my mother tongue, American-English.

So, I am currently on a mission to introduce the Danes to some rather more elegant, ancient English words and phrases. Like ‘flapdoodle’, which means nonsense. Or ‘hurkle-durkle’, an ancient word for one who prefers to remain in bed- ‘Eye-servant’ would work well for many of their civil servants - it refers to someone who only behaves properly at work when they are being watched. And when the government gives another press conference, perhaps they might employ ‘circumbendibus’, a 17th century word describing an answer to a question “so convoluted and evasive that it isn’t really an answer at all’, as British TV etymologist Susie Dent (from whom I learned all these) describes it.

I suppose there is one thing I should be grateful for in all of this. For now at least, there is one even more potent word that young Danes don’t seem to have learned about: the c-word.

Thank fuck for that.